|

| Solving everyday problems in Jenny Lives with Eric and Martin |

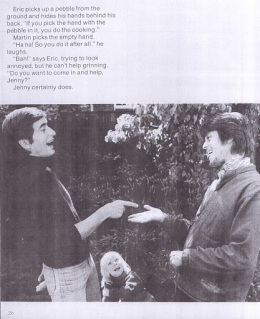

The picture above strikes me as innocuous, humorous and staged-looking; however, what looks kitsch today was implicated in significant moments in LGBT history and was part of a national controversy. In 1986, UK newspapers announced that a school library contained a copy of Jenny Lives with Eric and Martin, a fictional children’s book which depicts the everyday life of Jenny, a girl who lives with her dad and his boyfriend. Negative reactions to the publication are said to have led to Clause 28, which banned the “promotion” of gay family relationships in Welsh and English local authorities and designated them as “pretend”. Sparking protests from lesbians abseiling into parliament to street marches, it also inspired an array of artistic responses which challenged its assumptions. As an Art History student I recently had the fortune to look into two of these artists in particular, Sunil Gupta and Stuart Marshall. Gupta explicitly challenged the ruling in his photographic series “Pretended” Family Relationships, assembling both documentary photography and the lyrical. In a more comic vein, Stuart Marshall and Neil Bartlett’s film Pedagogue, executed in mockumentary style, highlighted the absurdity of the clause, subverted stereotypes and satirised paranoia around gay relationships and education. Both of the works, while very different, shake up notions of the image as “document” and made me think more about the complications of “representation”, particularly in the 1980s.

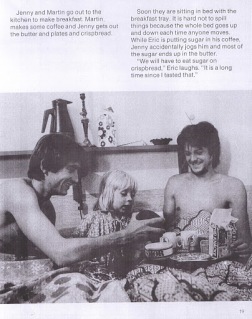

Originally published in Denmark and translated/reprinted by the Gay Men’s Press in 1983, Jenny Lives with Eric and Martin shows a variety of day-to-day activities such as the family having a birthday party, going to the launderette and playing “horse and cart”. The photo above shows a disagreement between Eric and Martin, during which both cannot agree on who should do the cooking; the argument is eventually playfully resolved by Martin picking which hand Eric has put a pebble in. The rather theatrical photographs in the book suggest the acting out of personal encounters, problems and resolutions, including both the humorous and banal aspects of everyday events. Nevertheless, in his article The book that launched clause 28, Adam Mars-Jones has written that, due to public outrage, the book’s actual contents were relatively ignored; he writes that it “has been reduced to an icon, represented only by its title and a couple of photographs reprinted in the tabloid press.” In Culture Wars: The Media and the British Left, Julian Petley also suggests the book was used by the Conservatives during the 1986 local elections to denigrate Labour and cites a number of quotations from officials at the time comparing the book with a process of force-feeding and brainwashing.

The controversy surrounding Jenny Lives with Eric and Martin brings to mind Simon Watney’s ideas around the ways in which the media presented homosexuality in relation to Aids in the 1980s. In Policing desire: pornography, AIDS and the media, Watney explores what he calls the “rhetoric of Aids,” discussing how it was “mobilised” to support anti-gay positions; he discusses how in the media at the time, the gay man was “effectively and efficiently positioned as he-with-whom-identification-is-forbidden.” By visualising Martin as both a partner to Eric and a father to his child, Jenny Lives with Eric and Martin draws attention to the diverse roles taken on by the character and so could be seen to complicate stereotypes around gay relationships. Watney writes of the ways in which “homosexuality” was used in the media to signify “promiscuity,” placed in opposition to the family. This is suggested by reactions to an image in Jenny Lives with Eric and Martin of the family having breakfast in bed together. Mars-Jones has written of a personal encounter he had where viewers of the book “would not be persuaded, in spite of the evidence of their own eyes — the yawns, the tray, the dolls, the lack of physical contact — that the scene of breakfast in bed was anything but an orgy. They would accept no other term for it. They were in a bizarre state that combined voyeurism and blindness”. This anecdote echos prejudices voiced in the media at the time which related the book to “perversion” and labelled it “vile” and sheds light on profound uneasiness around sexual identity. By referring to gay family relationships as “pretend,” Clause 28 seemed to presume that heterosexual relationships were the only valid basis for a family framework; however, Jenny Lives with Eric and Martin proposes the family as defined by interpersonal interactions, linked through shared experiences, rather the legal ties between married couples who define themselves as heterosexual.

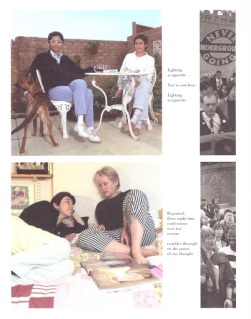

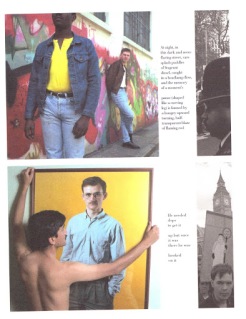

Sunil Gupta engaged with Clause 28 in his series of montages entitled “Pretended” Family Relationships, juxtaposing images of public and more domestic, private spaces. Consisting of three panels, each montage was assembled by hand and features representations of gay and lesbian couples, a section of poetry written by his partner at the time Stephen Dodd and black and white photographs of protest against Clause 28. In Pictures from Here, Gupta has written that the photographs in the montages referred “to the problematic nature of such documentary evidence”. He referred to the difficulty of finding “subjects of colour willing to be portrayed under a lesbian and gay banner” and that most of the couples represented were activists or artists, and not necessarily in a relationship, which problematises the status of the photograph as “evidence”. Gupta has stated:

“I have always felt badly served by the generally accepted notions of the history of photography. It never reflected my own life experiences, but rather a white, heterosexual liberal viewpoint; subject matter that was different always seemed to be treated in some particularly skewed way. Gay men, if depicted, were treated as perverted objects, fixated with the penis, and presented for a fetishized gaze. One looked without much success for photographs that depicted something of a gay man’s humanity and the everyday relationships that define him.”

How might we see the photographs in “Pretended” Family Relationships as challenging a “fetishized gaze”? Is it possible to relate the photographs to Judith Butler’s ideas in around the term “queer” as a “site of collective contestation, the point of departure for a set of historical reflections and future imaginings” (Bodies That Matter)? While Gupta has not labelled this series as specifically “queer”, Butler’s notion of the term prompts one to consider the image as resisting stereotypes relating to sexual categorisation. In relation to Gupta’s images, the couples often seem to be posed in potential relationship to one another; the colour photographs on the left evoke the sense of a momentary insight into an everyday situation and evoke the sense of a “snap shot aesthetic” (a term used by Keith Wallace to describe Gupta’s work).

Gupta also suggests the possibility for relationships to form in sites which are beyond the confines of the domestic space; for example, in one photograph a man glances at another who has walked past on the street. Situated between two images, the poetic text has a prominent part in the assemblages; by using imagery which does not seem to literally allude to the photographs, the poetry seems to undermine the idea that the photos could take on an illustrative function. The text often suggests feelings concerning relationships which elude direct relationality to the images and evokes the sense of both presence and absence; for example, in Untitled 7:

This brings to mind Sekula’s ideas in Photography Against the Grain around “bracketing” the photograph, using photographic texts with language to “anchor, contradict, reinforce, subvert, complement, particularize, or go beyond the meaning offered by images themselves”. Rather than using traditional family portraits, Gupta points to the many dimensions a relationship can take, and the unknowns which exist not only between the viewer and work, but between people in relationships.

The black and white photographs of protest against Clause 28 on the right of the montages also resist interpretation in relation to the poetic texts. Gupta has written, in Pictures from Here, that these images refer to the “necessity of political action”. Sekula’s text, which puts forward the political relevance of the photograph as “common cultural artefact,” argues against photography as a form of art seen as “ahistorical” and isolated from “social relations”. The photographs of street protest locate the images in a specific historical context; for example, the banners in the images complement the title of the series to draw attention to concerns around Clause 28, sometimes using references to wider cultural phenomenon. One banner reads “Never Going Underground” within the symbol of the London Underground; this was the symbol used by the North West Campaign for Lesbian and Gay Equality. Another banner uses the image of a rather disgruntled looking lollipop lady with the sign “Stop Clause 28,” perhaps referencing the ways in which the clause was implicated in local organisation of knowledge.

By representing people who identify as gay or lesbian in both personal and political situations, the work suggests the ways in which the spheres are interconnected. The work poses the subjects neither as victims of the law, but neither as idealised embodiments of “family”; they are also politically active. In this sense, it appears to be appeal less for what Enwezor calls the “moral imperative in the telltale details of the real” but for an engagement in the wider contexts of the image. Enwezor (in Documentary/Vérité: bio-politics, Human Rights and the Figure of “Truth” in Contemporary Art) writes of how documentary’s “complex variety of approaches” prompts a reconsideration of images beyond their “functionalist format”. Documentary and the archive are considered “tools” for “inducting new flows and transactions between images, texts, narratives, documents, statements, events, communities, institutions, audiences”. Gupta’s montages can be seen as a way of bringing together various formats which point to tensions in representing relationships; the poetic text asserts a sense of individual experience, intertwined with personal relationships and political action.

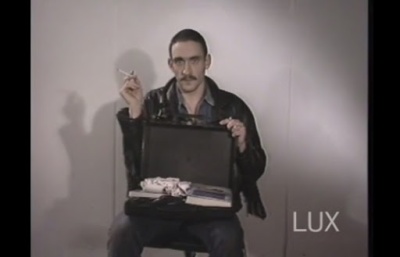

Stuart Marshall also challenged Clause 28’s terminology around promotion of homosexuality and media hype around this issue. His satirical video work Pedagogue (featuring Neil Bartlett as the main performer) consists of a mock interview with a teacher about his position at a polytechnic college and fake testimonies from students who have almost instantaneously changed their sexual identities as a result of his influence. The first part of the video work, Bartlett plays the role of a teacher in denial about his sexuality; the interviewer asks him a number of questions such as “what is your favourite colour?” and which appear to lead up to a main question of interest, “Are you a homosexual?” which he denies. The camera work suggests the satire of an interrogation, creating a build-up of close ups which progress from his eyes and eventually to his crotch. The interview suggests an increasing curiosity about the teacher which verges on paranoia; he is asked to reveal the contents of his briefcase, which include underwear, a fitness magazine featuring a half-naked man, and leather gloves. The extent of denial suggested both by the “signs” of homosexuality and the teacher’s repeated assertion that he is not a homosexual, adds to the humour of the work, which obviously plays with stereotypes around homosexuality and exaggerates them.

As the video progresses, a number of students speak about how they turned into lesbians after contact with their teacher. Their stories parody the idea of promoting homosexuality; not only do the women abandon fiancées and boyfriends, men turn into lesbians and cats of the same sex start acting “oddly” towards each other. The impact of the teacher is presented as spreading, threatening to destabilize relationships within an extremely short time. The series of revelations, as well as the questioning of the teacher, suggest an absurd exposé of brainwashing. The idea that the camera can be implicated in an attitude of suspicion, guided in order to uncover secrets, calls to mind Foucault’s ideas around “procedures of confession” in The History of Sexuality: Volume 1. Foucault writes:

“In any case, next to the testing rituals, next to the testimony of witnesses, and the learned methods of observation and demonstration, the confession became one of the West’s most highly valued techniques for producing truth.”

Foucault argued that confession has a crucial role in mechanisms of power and the discourse of sex, where “heterogeneous sexualities” are legitimised as part of a power relationship which require confession of desires beyond this heterogeneity. In this sense, could the documentary itself function as a device which prompts confession and unearths that which is suppressed? The mockumentary style of Pedagogue seems to parody this mechanism of confession seeking; the illogical causality between the teacher’s pedagogy and the students’ responses undermine the sense of a truthful narrative in the political context.

Clause 28 suggested that homosexuality as a term not only covered a homogenous group but also that this singular identity was marketed through representations of “pretended” families, in opposition to the supposed stability of the heterosexual, legally formalised family. Gupta’s montages suggest that identity is far more complex; the assembled fragments provide a sense of a multi-layered experience, eluding the sense of a finished or complete representation. With a more comic approach, Marshall takes the idea of threatening homosexuality to extremes, thus undermining the plausibility of the idea. While both Marshall and Gupta use different mediums and methods, their work highlights the complications involved in the viewing process and questions the viewer as a passive receptacle of propaganda, situating the work in a wider context of censorship and bringing the terminology of Clause 28 into question.